SynopsisSome law- makers even wanted to strip some of the legal protection the tech companies have from the majority of content posted on their platforms.

November has been an eventful month for people on either side of the free-speech debate. On November 17, the CEOs of Facebook and Twitter, Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey, respectively, appeared before the US Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions about their companies labelling content as “free speech” or “hate speech”. While the Republican senators questioned the platforms on censorship and anti-conservative bias, Democrats raised issues relating to content inciting violence and social unrest.

Some law- makers even wanted to strip some of the legal protection the tech companies have from the majority of content posted on their platforms. The free speech debate has become shriller in India also. The latest event that made people raise their voice was on November 21, when Kerala Governor Arif Mohammad Khan approved an ordinance — Section 118 A to the Kerala Police Act — that made “expressing, publishing or disseminating any matter that is threatening, abusive, humiliating or defamatory” an offence punishable with imprisonment of up to three years.

While the government said this was to protect victims of cyberbullying and online harassment, particularly women, activists and politicians of all hues alleged it left the field wide open for misuse and retaliation against any kind of dissent, much like Section 66A of the IT Act, which the Supreme Court had struck down as unconstitutional in 2015.

The new law was seen as a threat to free speech. Two days later, Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan said the state would not implement the law and a new one would be made after public consultation. Despite this temporary relief, the controversy captured the debate on the use of social media and the rights and responsibilities of technology giants operating such platforms. There are questions that everyone is trying to find answers to: Should these platforms be allowed to function freely as a market- place of ideas, information and opinion or should there be strict regulations around its use, keeping public interest in mind? Who will decide what is, and isn’t, free speech? After all, free speech for one could be hate speech for another. A new chapter in the debate started in India with the government in November bringing online news portals and content providers, including OTT platforms, under the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

This has raised the issue of censorship, especially after an FIR was filed against Netflix for hurting religious sentiment through a web series. What has become clear is that the hyper-partisan nature of the discourse is likely to escalate — both in India and globally. However, we are no where near to finding a balance between moderating content and allowing peo- ple the freedom to express varied views. Typically, these debates become grievances about specific instances where large tech platforms clamped down, or did not, on content that were supportive of a particular ideology. The November Senate hearing in the US was a testimony to that. Some say big tech has been too friendly to conservatives by allowing them to use these platforms as “megaphones for hate”, others accuse these companies of being biased against the conservatives. Then there are those who say content moderation is equivalent to censorship.

It often ends up with one side — to borrow an American parlance — being accused of “working the refs”, which is loosely defined as “an act to persuade the referee or other officials to view the players on one team with a sympathetic bias.” Within these contentious issues, the left and the right have broadly agreed on one thing: things have to change as far as big tech is concerned. The roles of these tech companies have been raised in the Lok Sabha too. BJP MP from Bengaluru South Tejasvi Surya said during a debate in September that there have been many “credible” allegations against these companies of “arbitrary and unilateral regulation and censoring” of posts by users, and especially those with a “nationalistic approach”. “This poses a significant constitutional challenge not only on the grounds of unreasonable restriction of free speech but also amounts to illegal interference during elections,” he added. The young MP has emerged as a leading voice of the Indian right against these platforms. Over the last few months, groups such as Citizens Against Anti-India Twitter, led by the BJP functionary Vinit Goenka, have been conducting regular webinars to raise awareness about Twitter’s alleged role in “anti-India activities”.

The participants, including activists and retired officials from the security establishment, have held the platform’s officials directly responsible for such lapses — one of it was about allowing an advertisement by a “pro-Khalistan” group. In May, Goenka filed a petition in the Supreme Court, seeking a mechanism to check Twitter content and advertisements that spread fake news through bogus accounts.

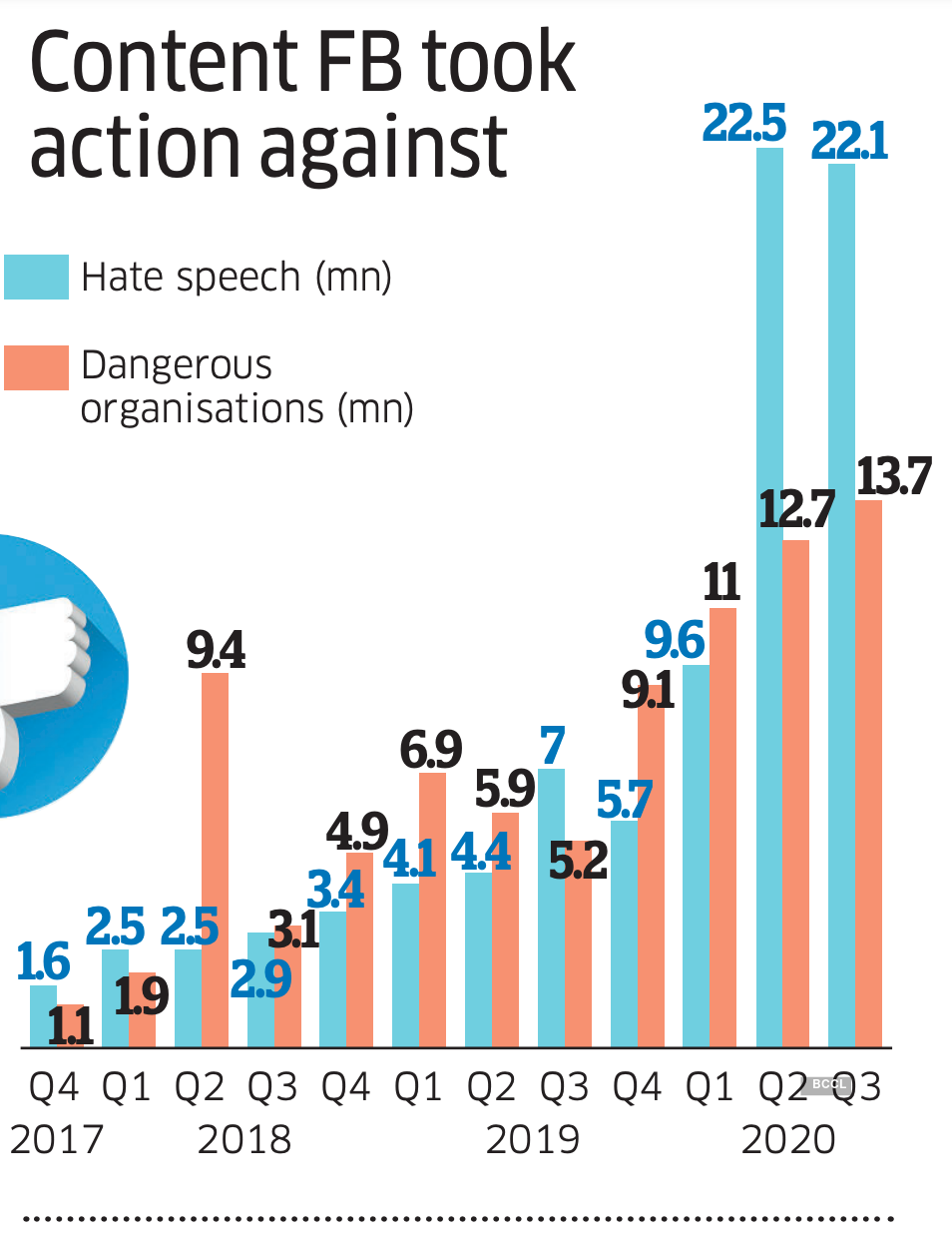

Facebook faced the heat in August when a committee of the Delhi government summoned its India Vice-President and Managing Director Ajit Mohan and other senior officials to ascertain if Facebook was used to incite communal violence in February. In fact, Facebook India’s policy head Ankhi Das resigned after news reports claimed the social media platform had not done enough to curtail certain “hate speech” comments. Mohan, its India head, has repeatedly said there was “no space for hate speech on our platform.” In a company blog, he wrote, “We have an impartial approach to dealing with content and are strongly governed by our community standards. We enforce these policies globally without regard to anyone’s political position, party affiliation or religious and cultural belief.” A 2019 report by US-based Equality Labs, focusing on Facebook India, found that 93% of all hate speech posts reported to Facebook remained on the platform. This would include content “advocating violence, bullying, use of offensive slurs, and all forms of Tier-1 hate speech.”

The report’s findings also stated that “nearly half the hate speech Facebook initially removed were later restored”. The authors wrote, “Facebook staff lacks the cultural competency needed to recognise, respect and serve caste, religious, gender, and queer minorities. Hiring of Indian staff alone does not ensure cultural competence across India’s multitude of marginalised communities. Minorities require meaningful representation across Facebook’s staff and contractor relationships. Collaboration with civil society and greater transparency of staffing diversity strengthens hate speech mitigation mechanisms like content moderation.” Facebook has since commissioned an audit of its activities in India to a US-based firm, from a human rights perspective.

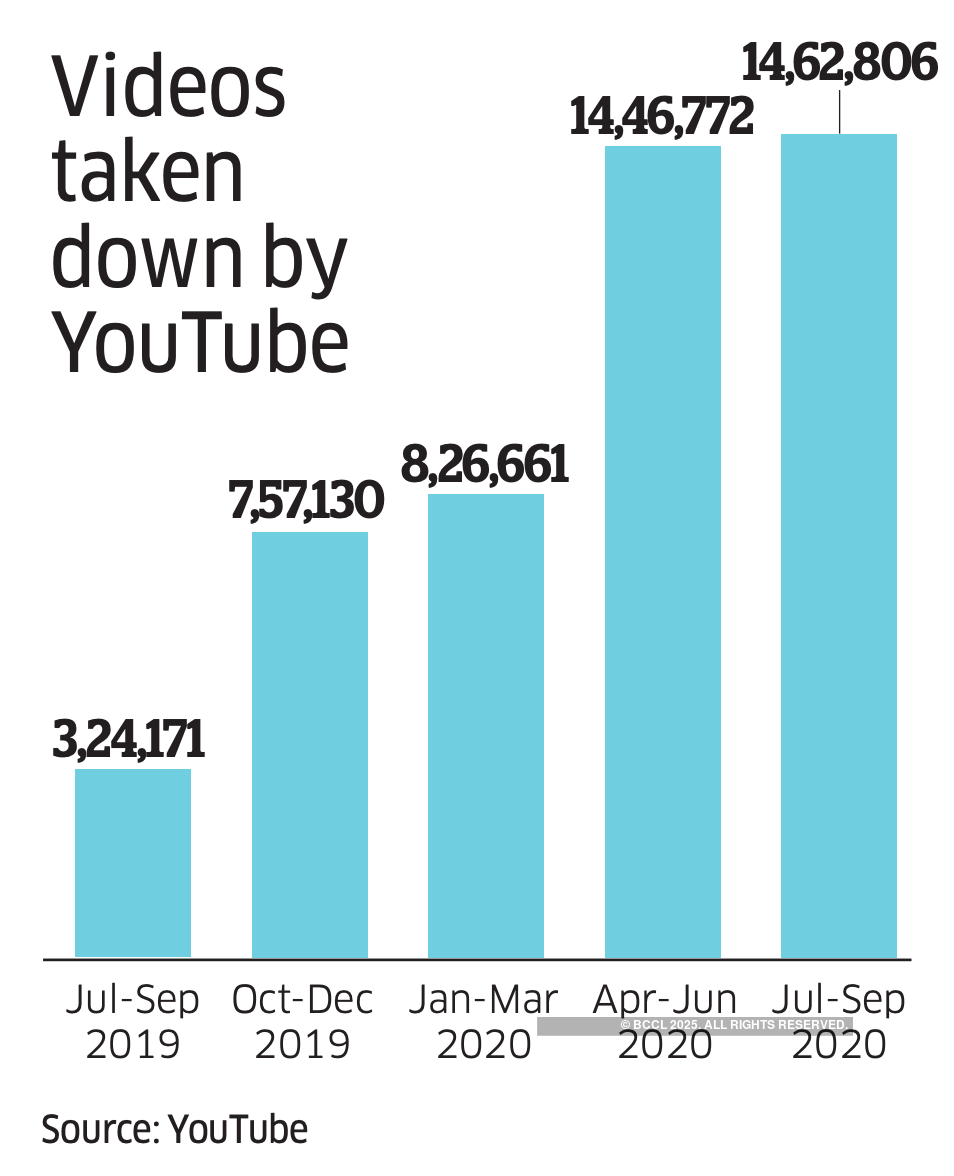

Responding to ET Magazine’s questions, a Facebook spokesperson says: “Billions of people use Facebook’s apps because they have good experiences — they don’t want to see hateful content, our advertisers don’t want to see it, and we don’t want to see it. There is no incentive for us to do anything but remove it. Where we find hateful posts on our platform, we take a zero-tolerance approach and remove them. When content falls short of being classified as hate speech — or of our other policies aimed at preventing harm — we err on the side of free expression.” A YouTube spokesperson says, “We believe that more information means more choice, more freedom and ultimately more power for people and that allowing individuals to voice both popular and unpopular opinions is important.”

However, there are critics who point to an “enforcement bias”. These companies do not have adequate mechanisms in geographies where there isn’t strict scrutiny, says a person who has worked in this domain. “Most of Facebook’s or YouTube’s actual content moderation is done by journalists. Unless there are PR crises, they just don’t bother,” the person adds on condition of anonymity. “In the US, they’re constantly under the microscope, not just from the media, but their own employees. That is not the case in India.” This shift in standards is not acceptable, say social activists. Kavita Krishnan, secretary of the All India Progressive Women’s Association, points to Twitter flagging up questionable tweats of outgoing US President Donald Trump as an example to emulate. “What they are doing with Mr Trump’s tweets when it comes to fake news, they should do it with every single leader, with everyone.”

In India, those in power can get away after making such comments. “The problem is that these corporations do not apply the standards the way they should — they apply it in certain cases very selectively and they don’t apply it in places where they think the balance of power lies with the offender,” Krishnan adds. Public policy professionals point out that even the community standards that Mohan referred to are not in sync with local realities — either in terms of representation or adherent to local law. But they acknowledge that Facebook had made progress in the region. The social media platform is not oblivious to local realities, claims Facebook’s spokesperson. “Our community standards are global, consistent with the global nature of our platform. We are constantly listening to and working with local experts to incorporate local context and nuances.

You Tube

When something on Facebook or Instagram is reported to us as violating local law but doesn’t go against our Community Standards, we may restrict the content’s availability in that country where it is alleged to be illegal.” One way to deal with shifting standards would be to have localised community guidelines, says Paul M Barrett, an adjunct professor of law at New York University. In an emailed response to ET Magazine’s questions, he says, “I think it makes sense for these platforms, which operate globally, to put in place country-specific, or perhaps regional, community standards that correspond to local values and legal requirements. As a practical matter, I assume that the platforms already must obey the local law in the countries where they operate.”

Beyond the specifics of content moderation, there is a perception that platforms are not doing enough to nudge their users to alter their social media behaviour. Raman Jit Singh Chima, policy director at Access Now, say, “WhatsApp has become a leading platform for information discovery. Has Facebook done enough on the literacy side nudge for good behaviour? No. It almost seems like they are very reluctant to take responsibility and change behaviour.” Chima uses an example of Facebook’s community standards to point out why the platform is not doing enough. The guidelines are available in English but it wouldn’t take too much to translate those into Indian languages, given that Facebook is widely used in the country. “This is low-hanging fruit. There is no reason why they can’t do it,” he adds.

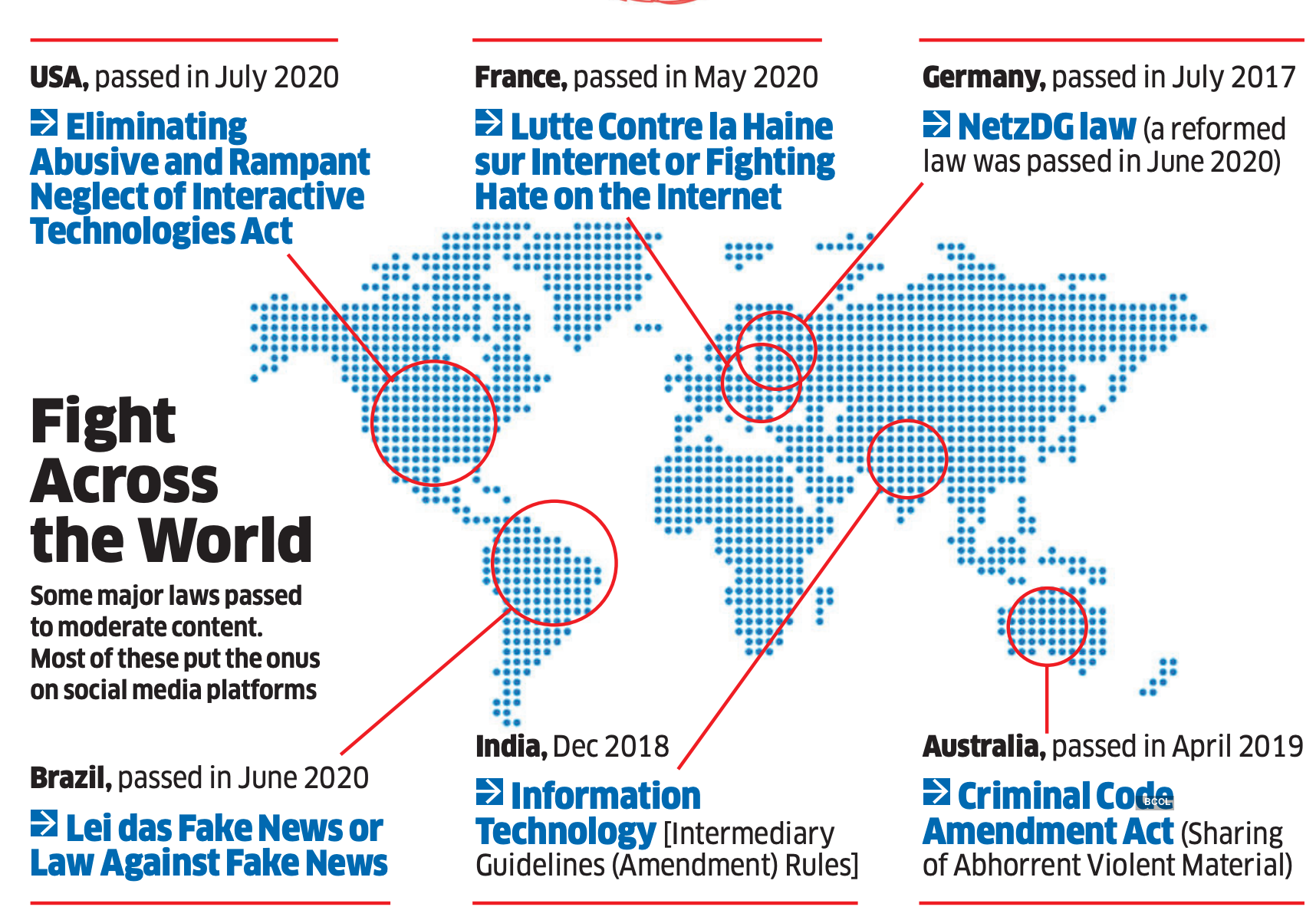

While governments across the world have understood the need for regulation, what they are doing might not necessarily be to clean up social media. “The real intent for governments is not to regulate big tech, but use that as a pressure tactic to seek more powers for itself, and put in place mechanisms that are not accountable — for instance, more automated tools, which they see as a silver bullet,” Chima says. “For instance, they used automated tools to counter violent extremism and child sexual abuse material. The same tools are affecting activists reporting or doing good work in these areas, like the White Helmets case in Syria.”

In western academic circles, there is a school of thought that such platforms do have an obligation to shape themselves and conduct themselves in a way that is deemed constructive for society, which effectively means self-regulation. To attract more users, the platforms will promote some degree of freedom of expression. But it cannot be an anything goes kind of freedom of expression. Barrett of NYU is optimistic of finding a balance in the free speech debate. “Generally speaking, I think it is possible to express one’s political, social or cultural views without threatening others or attacking core democratic institutions such as free and fair elections.”

He says newer social media platforms are likely to come up and people will migrate to those. “I am less worried than some other people about the future of free speech on the internet. There will still be plenty of outlets for political and social expression. Major social media companies are responding to outside demands for more content moderation, but I don’t see a major threat to free speech.”